Packages Research

The Walls and the Gates of Padua

|

|

On the other side of the bridge, to the right, there rises the so-called Ezzelino Tower (13th cent.), the external defence of the medieval walls. Following Piazza Mazzini and viale Codalunga the Bastione della Gatta is reached. Its name (bastion of the cat) derives from the fact that in 1509 the defe

From here the bulwarks Moro I, Moro II degli Scalzi and Impossibile can be reached, then the walls take to Porta Savonarola, dedicated to Antonio Savonarola, who won over Ezzelino da Romano at Arlesega. This splendid work, which plays with the chromatic contrasts of the Istria stone and grey trachyte, was made by Giovan Maria Falconetto in 1530. After the gate is the Savonarola bulwark, and a little further down is the bulwark of St. Prosdocimus. Further on is the San Giovanni Gate, another work by G.M. Falconetto with its namesake bulwark. Following via Cernaia and circling around the Saracinesca bulwark, visitors pass the small bulwark called Catena (or "chain": it blocked the entrance of water into the city) to reach Torre del Diavolo (the Devil's tower), the main remains of the defensive citadel built under the Carrara rule.

From here, the Paleocapa Riviera takes to the Astronomic Observatory called La Specola, erected by the Serenissima in 1767 on the Torlonga, one of the towers of the imposing late-medieval defensive Castle, enlarged by Ezzelino da Romano and renovated by the da Carrara family. The west side contains the third gate of the medieval city walls that used to give access to the Castle, while the 19th century building, now occupied by the Department of Astronomy, hides an important stretch of the curtain wall that, however, reappears a little further along to continue northwards, with various interruptions, along the Tronco Maestro canal. Following instead the course of the river southwards, and passing the Ghirlanda bastion, the Alicorno bastion is reached (visitors are allowed). It is the southern point of the defensive system of the 1500s. Having passed Trieste Park and crossed the square Santa Croce one arrives at the S. Croce gate (1527), over wh The pedestrian route that crosses the entire hospital block leads to via Giustiniani, then turns right to reach via Gattamelata, continues left along this street until the Cornaro Bastion, designed by Sanmicheli in 1539-40. From this point, along via Cornaro Street and then via San Massimo, the route takes to the crossroad with via Orus that offers a beautiful view of the old bridge of the Graelle (the metal sluice-gates of the Customs Office), near the confluence of the Santa Chiara canal with the Piovego and the Roncajette canals. Turning right at the end of via Orus, the tour continues along via Fistomba and on the Ognissanti bridge, which has a beautiful view of the Portello Nuovo bastions, of Castelnuovo (with the river gate originally installed for military purposes) and Portello Vecchio (all can be visited from via San Massimo).

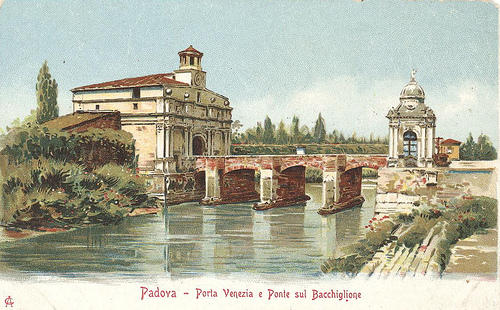

Across the bridge, the embankment of the Piovego leads to Porta Venezia (formerly Ognissanti gate). Built in 1519, perhaps upon the design of Guglielmo Bergamasco, it features a beautiful façade in Istria stone, supporting a clock tower. It is popularly called Porta Portello because here a small fluvial harbour existed, which was a stop for the boats navigating the rivers and canals that linked Padua and its county with the Venetian lagoon. A 1790 shrine dedicated to Santa Maria dei Barcaroli, where travellers attended mass before embarking on wood barges, still survives across the bridge facing the Gate.

Continuing along the walls and passing the Piccolo bastion, the route enters the park of the Arena with its bastion, and reaches the navigation lock and the little church of the Contarine locks (1723), an old interchange of river traffic. Its bridge and the one near the Grade del Carmine marked the point where waters leave town, and once these too were closed by metal sluice-gates.

|